Pork and Century Egg Congee

皮蛋瘦肉粥 (Pi Dan Shou Rou Zhou)

Congee, or rice porridge, is undoubtedly the humblest of rice dishes. To make congee, rice is cooked in a large amount of water or stock until the individual grains have nearly dissolved to form a thick porridge [1]. Congee was thus a way to feed an entire family using only a single cup of rice. Today, congee remains a popular breakfast dish, and is an easy-to-digest comfort food often served to children, the sick, and the elderly.

Congee can be made plain and served with side dishes, or flavors and other ingredients can be introduced to the rice itself as it cooks. One of the most popular forms is pork and century egg congee, which is commonly found at both congee shops and dim sum restaurants.

This dish features century eggs (皮蛋), a method of preserving chicken or duck eggs without refrigeration which dates back to the 15th century. Traditionally, eggs are coated in an alkaline clay containing ash, tea, salt, and quicklime and left for a period of weeks to months, a process which transforms the eggs and turns them dark brown [2]. The yolk becomes creamy, with a strong, pungent flavor, and the egg white turns into a savory jelly. When served on their own, century eggs can be an acquired taste, but they pack a lot of umami. Like anchovies in Italian cuisine, century eggs are often used as a seasoning in Chinese cooking, and when added to a big pot of congee they melt into the background, giving the entire dish an intensely savory flavor.

Ingredients

1 cup short or medium-grain white rice

4 cups pork or chicken stock

6 cups water

3 scallions, chopped

2-3 century eggs, diced

6 oz pork loin

1 tsp cornstarch

1 tsp soy sauce

1 inch ginger, julienned

¼ tsp white pepper

Salt to taste

In a large pot, combine 4 cups of pork or chicken stock with 6 cups of water and bring to a boil. Congee is best when made with homemade stock, as the rice will absorb many subtle flavors from its cooking liquid. If possible, I’d recommend a pork or chicken stock made with the classic Chinese aromatics—ginger, scallion, and garlic.

Now, let’s talk rice. Rice contains two types of starch: amylose and amylopectin. Amylose is a long and straight molecule which does not gelatinize during cooking. Amylopectin, in contrast, is a branched molecule which gelatinizes easily. It is amylopectin which causes rice to be sticky when cooked, and which is responsible for the thick, creamy texture of dishes like congee and risotto. There is more amylopectin in short and medium-grain varieties of rice, making them good choices for making congee.

When the cooking liquid comes to a boil, add one cup of rice to the pot. Simmer the pot for about 45 minutes, stirring occasionally. We want to cook the rice until it is very soft and the starch the rice has released begins to thicken the liquid. As the congee becomes thicker, it becomes easier for the rice to scorch on the bottom of the pot. To avoid this, we should stir more frequently as the congee thickens.

While the rice is cooking, we can prepare the other ingredients. To cut the pork loin into thin strips, first cut it against the grain into slices about ¼ inch thick. Then take the slices and cut them into strips about ¼ inch wide. Place the strips of pork in bowl and mix them with the cornstarch and soy sauce, then set them aside to marinate for 20-30 minutes.

Let us also take the opportunity to finely julienne the ginger, chop the scallions, and set these prepared aromatics aside. Then we can prepare the century eggs. Peel the century eggs the way you would peel hard-boiled eggs, then chop them into pieces, keeping in mind that the yolk will be sticky. If you like to have discernable chunks of century egg in your congee, keep the dice rather coarse. If you want the century egg as just a flavor, finely dice the eggs.

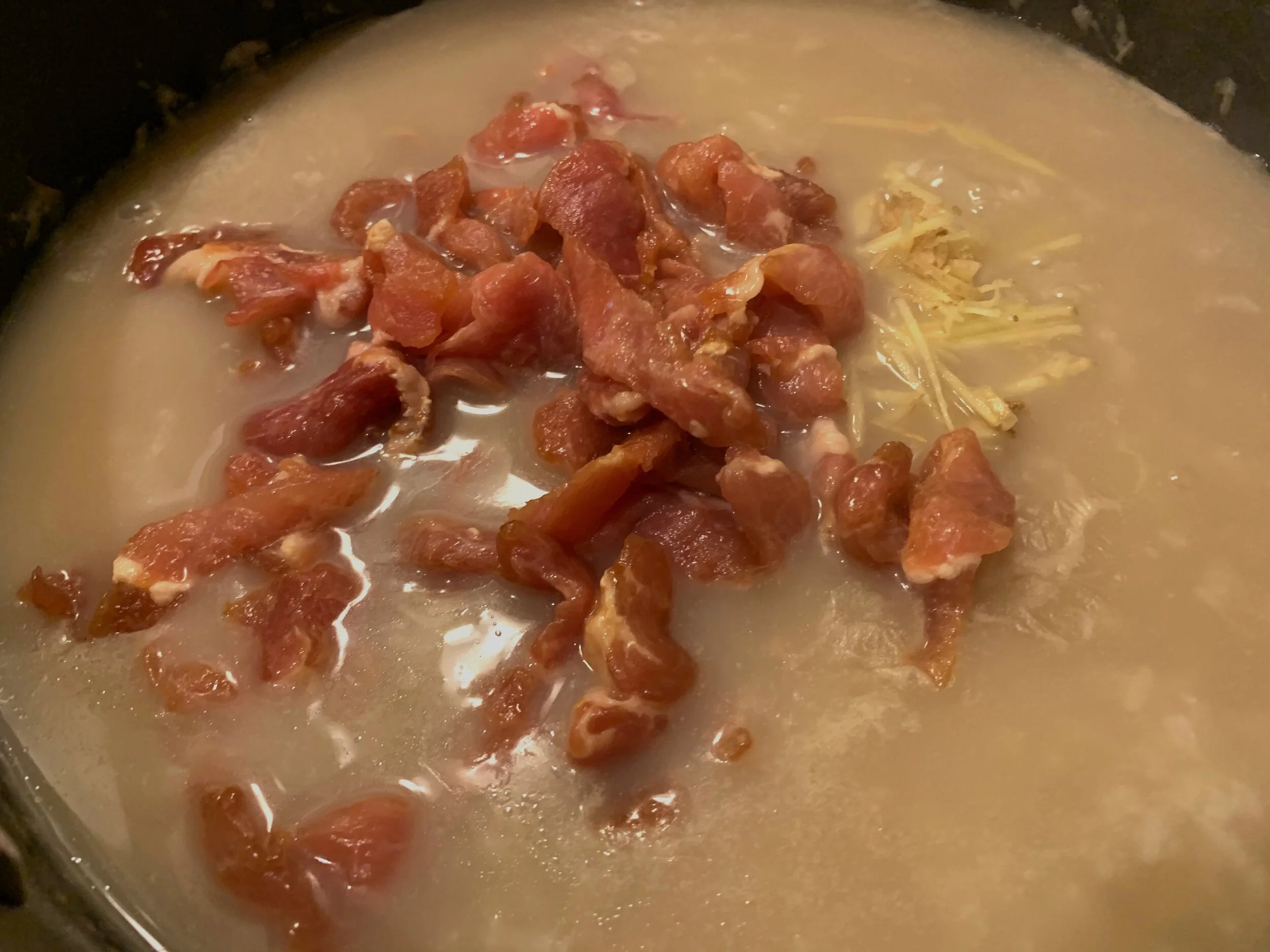

When the rice has softened to your liking, add the julienned ginger and marinated pork to the pot. Cook at a simmer for 5 minutes, adding water as necessary to maintain your desired consistency. Then add the diced century eggs to the pot. Simmer the congee for about 5 more minutes, stirring constantly, until the pork has just cooked through.

Season the congee with white pepper and salt to taste, mix in the chopped scallions, and serve hot. You can serve the congee on its own, but if you’re looking to serve it with sides, some common options are Chinese pickles, chili bamboo shoots, and youtiao (Chinese doughnuts).

Substitutions

It is possible to make congee with leftover cooked white rice. Simply use two cups of cooked white rice in place of the uncooked rice. Cooked rice will take much less time to soften, and will absorb less water, so reduce the additional water from 6 to 2 cups and reduce the rice cook time to 10-15 minutes. You can use cooked and shredded chicken or duck meat instead of pork in this recipe. You can also substitute Taiwanese minced pork if you’re in a hurry. You can add some pickled mustard (zha cai) to the porridge as well. As century eggs can be an acquired taste, you may choose to reduce the number of eggs you use in this recipe to one. Another option is to substitute century eggs with salted duck eggs, which are much milder in flavor.

[1] Cooking grains such as rice, wheat, corn, rye, or oats in water to make porridge or gruel is the easiest way to extract nutrition from starches. It therefore comes as no surprise that pretty much every Neolithic culture around the world has some form of porridge. In western popular culture, we have come to associate this sort of food with the poor and peasantry. In reality, however, gruel was eaten in Europe by members of all social classes, from Ancient Greek times all the way to the Victorian and Edwardian eras, even appearing on the menu of the RMS Titanic in 1912. Gruel has also survived in the food of the modern West, if you know where to look. Oatmeal, polenta, grits, kasha, and cream of wheat are all variations on the theme.

[2] This process is not biological fermentation, but rather a chemical reaction caused by the basic nature of the clay mixture, which raises the pH inside the egg to around 10 and causes some of the proteins and fats in the egg to break down.

Recipe

Prep Time: 5 min Cook Time: 1 hr Total Time: 1 hr 5 min

Difficulty: 1/5

Heat Sources: 1 burner

Equipment: pot

Servings: 6

Ingredients

1 cup short or medium-grain white rice

4 cups pork or chicken stock

6 cups water

3 scallions, chopped

2-3 century eggs, diced

6 oz pork loin

1 tsp cornstarch

1 tsp soy sauce

1 inch ginger, julienned

¼ tsp white pepper

Salt to taste

Instructions

1. In a large pot, combine the stock with 6 cups of water and bring to a boil. Add the rice to the boiling pot and simmer for about 45 minutes, stirring occasionally, or until the rice is soft and the starch has begun to thicken the liquid.

2. While the rice cooks, cut the pork loin against the grain into thin slices, then cut the slices into ¼ inch thick strips. Mix the pork loin strips with the cornstarch and soy sauce and let marinade for 20-30 minutes.

3. Peel and dice the century eggs, then set aside.

4. When the rice is softened, add the julienned ginger and marinated pork to the pot, and cook at a simmer for 5 minutes. If the congee is becoming too thick, add more water to maintain your desired consistency.

5. Add the diced century eggs to the pot and simmer for 5 more minutes, stirring constantly.

6. Season the congee with white pepper and salt to taste, mix in the chopped scallions, and serve hot.